CRAFTING OUR WAY OUT OF THE SHOEBOX

Inspiring footwear professionals for a systemic change in the industry through experimental studies, collaborating with local craftspeople and material designers.

INTRODUCTION

After having worked in the commercial footwear industry for many years, I started questioning why we make shoes such a complex product. The footwear industry generally uses materials sourced from all around the world, in which price plays the most important role. We look for the cheapest materials and labour, to sell shoes for an affordable price. This means that sometimes the material is purchased in one country, shipped to another country to stitch the upper and then send to yet another county to add the sole to it. Moving all these components around the world requires a lot of transportation and CO2 emissions. It was during my time at Loints of Holland that I realised it is also possible to source materials within Europe. For my master's research, I am exploring the possibility to prioritize the health of our feet and environment by using local resources instead.

For this research I approached craftspeople with various specialities. I visited their workplaces to understand their craft and get an insight into the materials and techniques that they work with. Based on these insights I made prototypes of shoes, which I then used as conversation pieces.

I collaborated with a basketry artist, taxidermists, traditional tanners (bushcraft), but also with material designers that work with human hair as a raw material. My role in this is to translate the material and techniques to a final product.

My goal is to inspire footwear professionals for a systemic change in the industry through experimental studies, collaborating with crafts people and material designers.

During my research I actively worked with and broadened my network. The pieces I crafted during my master's studies serve not only as tangible expressions of my findings but also as ongoing catalysts for dialogue and further research.

My aim is to combine my passion for footwear, education, and research. This approach allows me to follow my passions while also making a positive impact on the industry and inspiring others to do the same and think outside of the (shoe)box.

BACKGROUND

Working in the footwear industry means you have to deal with suppliers a lot. Leather, textiles, microfiber, PU, EVA, TPU are just a handful of the most used materials in shoes. All these materials come from different suppliers, in different countries. On top of that, it is not just the transportation that leaves a footprint, but also the ingredients itself. A lot of materials used in footwear are petroleum based. For example, polyester, polyurethane (PU), microfiber and even the finishes on leather can be petrochemical.

Within the shoe industry, it is a given that shoes are made in a certain way. It requires specific tools like lasts, stitching machines, and sole presses, as well as predetermined materials like leather, rubber soles, thermoplastic reinforcements, etc. These elements are essential for creating footwear that conforms to standard designs, such as Chelsea boots, loafers, pumps, or sneakers. Certain ‘rules’ apply to the technical design of these footwear archetypes. I remember fondly that my pattern making teacher once explained that a certain dimension needed to be seven millimetres, when I asked him ‘why’, his answer was: “that’s just how it is”. These rules in material, design and technical development are taught to us in school. But in order to innovate, these rules need to be let loose.

The challenge is in the system, the footwear industry. The system is where inputs enter, like material and design decisions. The system requires a change, to make room to innovate on real sustainability or circularity. No matter what kind of materials are decided on in the design process, according to Asher Clark, founder of Vivobarefoot[1], the shoe should be as simple as possible and be made out of a mono material. When designing a shoe, it is easier to make a complex product. You can find a solution for everything. Need a water repellent shoe? Just add an extra membrane. Eyelets tear the leather? Just use some reinforcement. To design a simple shoe, or even a mono material shoe is way more difficult.

After the industrial revolution, shoes became a bulk commodity. Everything was possible. When the running hype started in the seventies, athletic shoes for the general public were developed. These shoes were developed for people that normally wear dress shoes and never ran before. They started having injuries and that’s when heel counters and arch support were added. They are adding band-aids to the effect of creating a problem with the heel (Mike Friton, Shoespiracy)[2].

When designing a shoe and developing it with a shoe factory, a Bill of Material (BoM) is being used. This document is like a recipe for the shoe, each component is described including colour or article codes and supplier. People that buy shoes often have no idea about how many and which components go into a shoe.

[1] Asher Clark, The Future Of Footwear, in The Foot Collective ‘Restore to Explore’ Podcast, season 3, March 26 2024 (https://community.thefootcollective.com/podcasts/restore-to-explore/episodes/2148573957)

[2] Mike Friton, in Vivobarefoot, Shoespiracy March 20, 2019 (https://youtu.be/x_rDFa6kZfI?si=_W3-YLcH4NqhXAfR&t=277)

FEET AND FOOTWEAR

The foot

The focus of this research is mostly on material. However, when thinking about material for footwear, the foot should not be forgotten. A material should enhance the comfort of our feet. For that reason, in order to research material for footwear, the function of the foot should be studied first.

Footwear is part of an unbroken proprioceptive loop, which connects our brain to the earth. Information we receive from our feet, is being translated into signals. The choice of material will also have a significant impact on the proprioception that is experienced. As an example; you are strolling through the forest, wearing your most sturdy hiking boots. With each step, you encounter the uneven terrain, until suddenly, you feel a sharp pain shoot up your leg as you step on a tree root. The stiffness of your boots is relentless, causing your ankle to strain. But what happens if you are strolling through the forest barefoot? You encounter the uneven terrain and your foot senses the presence of the root beneath you. Without the constraint of sturdy footwear, your foot instinctively adjusts, wrapping itself around the contours of the root, sparing your ankle from further harm. This means that with minimal material around our feet, maximal proprioception can be experienced [1]. The choice of material for footwear is crucial for several reasons, as it directly impacts the comfort, durability, performance, and overall functionality of our footwear.

In footwear it is often said that the last comes first. A shoe last is an abstraction of the anatomical shape of the human foot, it is a solid form around which the shoe is made. The starting point for shoemaking is therefore always a last. Fashion often also plays a big part in the shape of the last, for example pointy high heels. In some cases, the foot then has to form to the last, squeezing our toes together. If we take a look at indigenous footwear, we learn that these shoes are often made around people’s feet, using locally sourced material [2]. The research of Willems et al. compares three types of indigenous footwear; an Indian buffalo leather sandal, a Scandinavian reindeer boot, insulated with dried grass and a Namibian sandal made out of antelope skin. These types of indigenous shoes are then compared to a commercial minimal shoe from Vivobarefoot and the participant’s own conventional Western shoe. It concludes that all indigenous footwear can be considered as functional as commercial minimal footwear. They can all be considered minimal functional footwear, with some differences to barefoot walking.

[1] Catherine Willems, Feet and how to shoe them, in Els Roelandt, e.a. (ed.), Do you want your feet back (APE, 2018 #122), p.26-51

[2] Willems C, Curtis R, Pataky T & D’Août K ,2020, Plantar pressures in three types of indigenous footwear, commercial minimal shoes, and conventional western shoes, compared to barefoot walking

As an introduction to my research, I initiated an examination of people’s feet in comparison with their respective footwear. An initial observation shows the constriction experienced around the toes and the metatarsal/forefoot region (ball of the foot); an area vulnerable to the development of bunions. The accompanying visual representations show the difference between the contour of people’s feet and that of their shoes and/or inner footbeds. When compared to the shoes, it should be considered that the outline also contains extra material such as upper leather or soles, which means less space inside the shoe.

When walking, another factor plays a big part in the relation between our feet and shoes. While we walk, our feet elongate and need more space. The images below show the results of the difference in the participants’ footprint while walking or standing still. The difference in length of the footprints varies between ten millimetres and twenty-five millimetres.

These iterations, combined with the paper by Willems et.al. and my experience working in the industry, confirm to me that the traditional western shoe making is not necessarily beneficial for our feet. We often choose fashion before performance. The foot should come first and when using a last, the last should resemble the foot and not be a fashion influenced shape. Let the feet shape the footwear, not the other way around. For that reason, all shoes made for this project will be made around either my own feet, a 3d printed copy of my own feet, or a barefoot type of shoe last.

The making process

In Western culture and society, we have lost connection the materiality in fashion. After the Industrial Revolution, footwear became a bulk commodity. We have lost touch with how the things we wear are made and where material comes from.[1] We no longer know where the material comes from that our shoes are made from. We even do not know who the person is that made our shoes. With the introduction of the shoe last, shoes are no longer shaped for our unique feet, but are moulded around a simplified shape of the average foot. However, according to the Future Footwear Foundation, traditional types of handmade, bespoke, and eco-friendly footwear is considered ‘new-luxury’. [2]

The oldest shoe ever discovered dates back to around 5000 years ago. This shoe is made from leather and plant fibers and provides evidence of early efforts to create protective footwear. The leather is moulded around the shape of the foot and hay is inserted to add comfort and insulation. A very minimalistic product if you compare it to modern day sneakers. [3]

Current footwear does not only affect our proprioception and anatomy (think about the bulky, heavy soled sneaker trend) but the production of it also damages our planet. We need to reconnect with our planet, both literally and metaphorically speaking. Can we use local resources to reconnect with our planet again?

With my research I am aiming to Inspire footwear professionals for a systemic change in the industry through experimental studies, collaborating with crafts people and material designers.

[1] Dr. Danielle Bruggeman, Moving beyond ego, in Circular Fashion: Design, Science and Value in a Sustainable Clothing Industry, WageningenX FASH01x (EDX, 2023)

[2] Christine de Baan, Foreword-Future Footprint, in Els Roelandt, e.a. (ed.), Do you want your feet back (APE, 2018 #122), p.26-51

[3] Footwear design then and now, Aki Choklat, Footwear design (Laurence King, 2013), p 10-12

METHODOLOGY

For this research project, I connect with local craftspeople and material innovators to explore new or alternative ways of shoe making together with them. These people are generally incredibly open minded and inspiring, and have the ability to think outside the (shoe)box. They have a certain skillset, but can also think creatively and create something with their hands. This chapter will explain more about the research method and tools that were used in order to conduct this research.

Research design – ILUPE

The research method that was developed is something that happened naturally. It emerged from my own, personal way of working. After a few iterations, it became clear that there was a methodology behind my way of working. This is how the ILUPE method came about. The prototypes in the next chapter were all created through this method.

Identify

Identifying works in two ways. It is about identifying materials, but also identifying local crafts. In this first part desk research takes place. You have researched local shoemaking, material sustainability or anything that interests you. Once you have identified your topic (this can be a certain material or technique), you start looking into experts on this topic. For example: my desk research made me interested in how I can translate ancient woven sandals to something that I can create in my local environment. I contact a local basketry artist as an expert, because they know everything about weaving and braiding with plant material.

Learn

Once the crafts or materials and experts are identified, it is time to build a connection with them and learn about their background and passion. Not everyone is eager to share their knowledge with a stranger, but many craftspeople host workshops or courses. This can also be an effective way to learn some techniques and get to know people within this field.

Understand

Spend time with your expert in their workshops to gain an understanding of the materials and techniques they work with. Practice with the materials or try alternative materials that can be used with the techniques they taught you.

Prototype

Create prototypes with the finding done so far. Which materials work? Which techniques work? These assets can then be used as tools to create a prototype.

Evaluate

Feedback and evaluate the prototype. What can be learned from this prototype? Did it inspire to improve the concept? The prototype can now also be used as a conversation starter, to explain people about the project.

CRAFTED FOOTWEAR PROTOTYPES

In this chapter several iterations will be describes and explained. These iterations were all done through the previously explained ILUPE method. Crafts and techniques were explored and in some cases a product was made from the explored techniques and materials.

Basketry

One of the most obvious crafts to start researching, was basketry. Basketry, or braiding plant material in general, is a technique that is used in historical and ethnic footwear a lot.

When I first started this research, I came across an exposition in Brussels called ‘Nizhónígo Yííkado - We walk in beauty’. This collaborative event was initiated by Catherine Willems, founder of the Future Footwear Foundation and was a collaboration between Native American performers, artists scientists and researchers working in Belgium. At this event I was introduced to ancient yucca leave sandals as found in the Southwest (US). Benjamin Bellorado, one of the contributors, is an anthropologic archaeologist who researches ancient footwear. He explained that this yucca leave sandal is an essential thing to survive. Everyone within the community knows how to make this type of footwear, in case they ever get lost in the forest for example. They steam the leaves to soften them, which makes it easier to braid into a sandal. Yucca leaves work well in footwear because they offer padding, thus comfort. On top of that, it is also a material that preserves well. Willems added that in some areas in Colombia they make a similar type of shoe and dip it in rubber, from local rubber trees, to make them waterproof. In these regions a leather shoe for example would mould due to the humid climate. They make shoes with the materials they are surrounded with, for the environment they are surrounded by.

A great principle, making shoes with plants, which you are surrounded with. I wanted to find out if it was possible to translate these principles to my own environment. I made an appointment with a local basketry artist to explore the available local plant materials and the braiding techniques required to work with this material. Mieke Langenhuizen is a very skilled basketry artist, who grows a lot of the materials she uses in her own garden. She works with many different materials, for example birch bark, willow bark and rush. Birch bark is a firm but flexible material. It can be softened by heat due to the tar that is inside the bark. Willow bark on the other hand is a very stiff and hard material, which can be softened by soaking it into water. Rush is a very fragile material, which can also be softened by soaking it into water. This makes it flexible and therefor can be braided in a very tight and firm way.

Wet weaving and braiding rush together with Mieke Langenhuizen

Because of its flexibility and ability to form a fine and firm structure, the first iteration is done using rush, coming from the Dutch wetlands. First the rush needs to soak in water to become flexible and stronger. When it dries out, it will break in the weaving process. Once woven, braided, or twined, the construction is strong and can dry out without breaking. The bottom of the shoe is constructed using the plaiting technique. Then the ends are twined around the rectangular bottom and find its way up around the shape of the foot.

This shoe is still very fragile, especially to walk on rough surfaces. For that reason, I also applied this technique and material on an already existing sole. I used a polyurethane (PU) sole which is designed for disassembly; meaning that it is easy to separate multiple materials and reuse or recycle them at their end of life. This sandal is only plaited, the advantage of this is that the ends can be pulled or loosened easily while they are still wet and therefore can be fully adjusted to an individual foot, even when it is made on a generic shoe last.

The sole is wearproof, but not locally made. This brought me to the most well-known Dutch shoes; wooden clogs. Clogs can last a lifetime and are traditionally made of locally sourced willow and poplar wood.[1] I contacted Marijke Bruggink, who is researcher and coordinator at Schoenenkwartier (the Dutch shoe museum) and Ambachtenlab (craft lab). She also collaborates with clog makers around the country and offered me a pair of wooden soles. The style made on this sole is similar to he PU sole.

[1] Europese klompen geschiedenis en verscheidenheid, Ted de Boer – Olij (South Sea International Press Ltd, 2002)

Traditional tanning

Oldest shoe discovered, made from leather and hay

Having worked in a Dutch tannery for seven years, leather and skin is something that fascinates me. Tanning hides and turning them into leather is an ancient practice that dates back thousands of years. The oldest shoe ever discovered dates back to around 5000 years ago[1]. This shoe is made from leather and plant fibers and provides evidence of early efforts to create protective footwear. The leather is moulded around the shape of the foot and hay is inserted to add comfort and insulation. A very minimalistic product if you compare it to modern day sneakers.

My work experience in the leather industry taught me the principles of making leather on an industrial scale. The hides have been in many people’s hands before it is even turned into leather. Leather is a commodity and still today many people have no idea where it comes from. Dairy cows, primarily raised for milk production, must bear calves to lactate effectively. Once the calves are born, they become a by-product of the dairy process and are subsequently utilized in the meat industry. The hides from these animals, in turn, become another by-product of the meat industry, contributing to the leather production chain.

[1] Footwear design then and now, Aki Choklat, Footwear design (Laurence King, 2013), p 10-12

But what if we make our own leather? I wanted to find out if it was possible to make my own leather from local animals. Under very strict circumstances hunting is allowed, because of population management. The deer go to the butcher and the hides are usually thrown away. Only a few people still use these hides. I came in contact with Thijmen Apswoude who is a bush crafter, specialized in traditional tanning. I joined one of his courses on traditional buckskin tanning.

Tanning is a method to preserve animal skins. Not just skins can be preserved, everything that contains collagen can be tanned. When tanning wild animals, it needs to be considered that there is a difference in the animals’ skin in summer and winter. In summer animals usually have a thicker skin and thinner fur. While in winter they have a thinner skin and thicker fur.

A skin consists of three different layers. The epidermis, the outside part of the skin which is in contact with the air. Then there is the dermis, the thickest layer. This layer is what is used to make all kinds of leather. The deepest layer is the hypodermis, which consists mostly of loose connective tissue and fat. This layer is always removed when making leather.

The buckskin tanning process happens in 10 steps:

1. Fleshing – removing the membrane, meat and fat of the hypodermis. This is important to do fast, to reduce the risk of rotting.

2. Bucking – soaking the skin in a solution that contains water and wood ashes, in order to dissolve mucus (gelatinous substance produced by mucous membranes). This makes it easier to remove membrains and hairs.

3. Graining – Removing the outside grain, the epidermis and also the hairs and follicles.

4. Rinsing – Hanging the skin in running water, to remove the dissolved mucus.

5. Membraining – Scraping the skin on the inside (fleshside) to remove membrains.

6. Acidifying – Neutralising the PH to approximately 3 with natural vinegar, this makes it easier to soften the skin.

7. Wringing – Removing just enough water in order to absorb the oils in the next step.

8. Dressing – Impregnating the skin with oils, traditionally this part is done with the brains of the animal. In principle, each animal has enough brains to use in this step of the tanning process. Alternatives can also be used; egg yolks, liver or a combination of sunflower oil and detergent. It is important to massage the dressing substance in the skin. Step 7 and 8 can be repeated multiple times if needed.

9. Softening – at this stage the skin is still moist, because of the dressing. Now the skin needs to keep on moving, so there will be no time for the fibers and collagen of the skin to stick together.

10. Smoking – formaldehyde in woodsmoke builds bridges between the fibers, which keeps the skin from hardening.

After going through all these steps, which will take a minimum of three to four days, the result is a soft piece of leather. This leather can then be used to make something from it. Traditionally buckskin is used for clothing and is still used for this in bushcraft. The ‘rules’ say that it is too thin for shoes. Since my inspiration was a one piece material shoe, I decided to make something similar. What is interesting to see is that after wearing the shoe for a day, the footprint became visible at the bottom. This shows that it is almost a barefoot experience walking on these shoes!

Taxidermy

Working with skin also led to another path, as there are many more animals, which at a certain point come to an ending of their live. Seeing a lot of roadkill on the way to my office, made me think about what happens to these animals. Leather is still the most used material in footwear, but it is more and more criticised. As long as we eat meat and consume dairy, there will be leather. But what about all the animals that die at the vet, through pest control or as roadkill? Is it more, or less ethically responsible to use the skins of these animals for leather?

At the shoe museum in Belgium (Shoes or no Shoes), I came across this pair of toad shoes. The vamp is decorated with toad skin, in which the head of the animal is prominently placed in the centre. I wanted to translate this idea to our local ‘pests’ and find out if it is possible to make a shoe using the skin of these animals.

Bos & Fauna is a Dutch organisation for taxidermy that offers courses and workshops in this craft. I took a beginner’s workshop in mammal taxidermy, in which I prepared a mole. The moles used for this workshop come from pest control, for instance when someone calls the pest control services because they have many molehills on their green lawn. The animals are cremated or otherwise used for taxidermy. Moles have a beautiful full fur, and their skin is quite strong. On the downside, they are small animals and if you would use their skin to make a shoe, one skin is not enough.

Through Bos & Fauna I got my hands on 3 moles to work with, after the workshop. I learned how to skin the animals and preserve them, the next step is to see if it is possible to make a shoe from them. Skinning the moles, takes some practice, but can be done in approximately fifteen minutes per animal. In taxidermy, the skin is not tanned, but preserved. This means that the bacteria are killed and the skin is then dried out. When the skin is dry, is also becomes hard and stiff, like parchment.

All three moles were used to create one shoe, which was moulded around the foot shape. The skins were sewn together while they were still wet and slippery so they could dry up in the shape of the foot. It became a very fragile ‘shoe’, because the skin is very thin and delicate. However, it is a great piece to discuss the possibilities and limitation we have on using animal based material.

Intestines

While I was researching traditional tanning, I came a cross the bushcraft principle of ‘using the whole animal’. The idea is that nothing goes to waste and when you kill an animal for its meat, you also use all the other parts. This principle got stuck in my mind, but only became a clear idea when I visited Mieke Langenhuizen again. She was making an art piece using pig intestines. The beauty of intestines is that they shrink when they dry out. I imagined this could work out nicely when braiding the material around the shape of a foot.

Knowing the braiding techniques already from previous iterations, I wanted to implement the same braiding style with a different material. When shrinking, it would create an open structure. I contacted a butcher to get some old cow intestines, which they normally use for sausages. The intestine is salted, so needed to be rinsed thoroughly first. Initially I did not rinse enough, meaning it would not dry out properly. After braiding I gave it another rinse, after which the shoe started drying out well.

The shoe became a very odd looking thing, of which the touch and feel is often described as ‘a dog treat’. Because it is dried out, it is really hard and stiff, but not unwearable. However, when soaked in water, it becomes soft again.

Human hair

Something that also caused a lot of discussion was the experiments with human hair. In the Dutch shoe museum (Schoenenkwartier) I came across a shoe that was made from human hair and emu feathers. The description said nothing more than a ‘slipper offering magical protection’.[1] Human hair was already a material that caught my attention before, but I never saw it being used on footwear. Later on, while visiting Shoes or No Shoes (shoe museum in Belgium), I saw the same type of footwear on display.

[1] Aboriginal Australian shoe, Karara, 19th century, Schoenenkwartier Waalwijk on loan from Stichting Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen, 2023.

Here it was explained that these shoes have an awfully specific purpose. They were made to sneak up to someone very quietly. Among the aboriginals this shoe was made by executioners, who had to track down and hunt a criminal who had received death sentence. They braided human hair, kangaroo fur and emu feathers into a bird’s nest looking shoe. The design of this shoe thus has two beneficial properties for this purpose; on the one hand it is a very quiet shoe, the criminal will not hear that someone is creeping up on them. On the other hand, because of the structure on the bottom of the shoe, the executioners would not leave a trace. [1]

[1] Australia and Pacific, William (Boy) Habraken, Tribal and ethnic footwear of the world, Export promotion international

Human hair is something we throw away a lot. People go to the hairdressers and get hair cuts or, as a person with long hair, you find your strands left behind in a hairbrush or find them in the shower drain. This is mostly seen as waste, but it is also a raw material. Realising this, inspired me to go and search for ways to use human hair.

Human material loop is an organisation which uses human hair and turns it into textiles. They collect hair from hair salons and then tread the fibers so they can eventually be turned in to durable and natural textiles. This project is lead by Zsofia Kollar, but there are actually a lot of people working with or researching human hair. That is also how I got into contact with Sanne Visser, who is doing PhD research in London. She also collects hair from hairdressers, treads it and then makes super strong rope out of it. I participated in her workshop at the Wereldmuseum in Rotterdam and experienced what it is like to make ropes with human hair. The piece of rope that I made with Sanne, inspired me to make a shoe with (potentially) human hair rope.

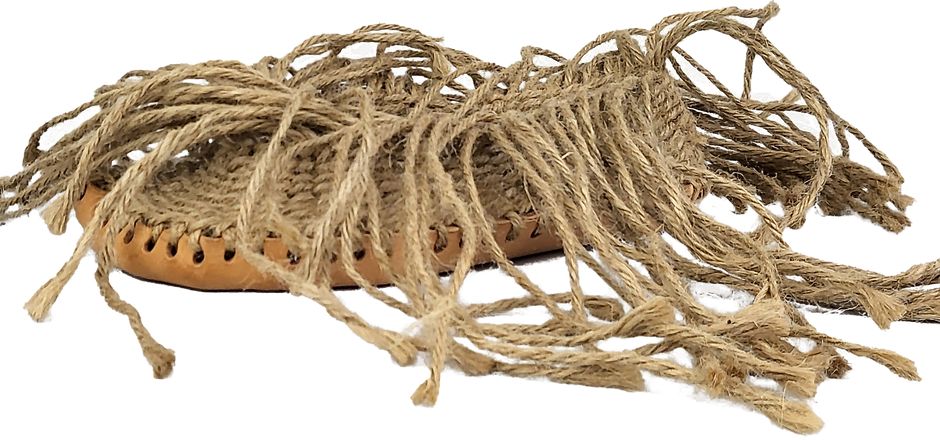

Since human hair is no commodity (and it should never become one!), currently I am still collecting hair. However, in order to experiment with the idea of human hair rope, I worked with a jute rope as a replacement. Rope can be used in a similar way than the plant material used for basketry. After the rope is made, it can be braided around the shape of the foot.

CONCLUSION

The goal of this research is to strive for a systemic change within the shoe industry, as currently the shoe industry is not only polluting because of all the different types of material but also the fact that these materials come from all around the world. Several experimental studies are done with the purpose of inspiring footwear professionals to think outside of the conventional (shoe)box.

By collaborating with various local craftspeople, some unexpected materials can be turned into footwear. The most potential in terms of techniques, comes from basketry. The basket weaving and braiding techniques can not only be done with plant material, but also with other material such as leather, hair and even intestines. Not all material will become a successful shoe, this depends a lot on the circumstances the shoe will be in and the purpose of the shoe.

Collaborating with various other makers, designers and experts, gave some very interesting insights. Often one iteration led to another one, but also the discussions that came of out this are very valuable. For instance showing the taxidermy (mole) shoe, usually raises a lot of questions. This shoe turned out to be a great conversation piece to start the conversation about the leather industry and raise awareness about the materials that we use in footwear.

This research shows that a shoe is more than just the archetypes that we are familiar with. It is not a necessity to have a separate sole and upper. Mono-material shoes are the most environmental friendly, but also the most difficult to make, as you cannot just use another material to fix a problem that occurs.

Not all the materials within this research have been successful for a full shoe. However, all of them are interesting for implementation. The most complicated part, is the part that touches the ground. If the shoe needs to last a longer time, the material has to be very durable. All materials can be used for the upper part, but from the materials in this project, only leather is suitable for a full shoe. Therefor it can be said that upper material is easily replaceable for a local material. The sole is a lot more difficult.

Important to note is that many of the experiments that are done are quite extreme, in the sense that it would not be realistic to make these shoes for use. This is in line with the objective of the research to inspire footwear professionals to think outside of the shoe box.

Future research will have three different focusses. First of all is to expand the range of material. There is so much more to explore, for me personally the next step is at Aalto University where I will follow a course in Nordic Biomaterial. Secondly, there will be an extra focus on material for a ‘sole’ part. And lastly the material research will be translated into actual, wearable shoes.